|

SEP 09, 2001

Solar Power Is Reaching

Where Wires Can't

By DAVID LIPSCHULTZ

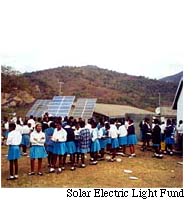

Two hours outside Durban, South Africa, deep in the Valley

of a Thousand Hills, Myeka High School had no electricity. Students

struggled to read by candlelight, and few textbooks and newspapers

were available. The school was clearly having a hard time doing

its job: only 30 percent of the students graduated, and even

those had little hope of going beyond their isolated village.

Then, in the spring of last year, solar energy came to town.

Photovoltaic solar panels, firing up 2.4 kilowatts of power,

were brought into the school by the Solar Electric Light Fund,

a nonprofit group based in Washington. SELF also persuaded Dell

Computer and Infosat Telecommunications to donate computers and

a satellite uplink so that the students could have Internet access.

Now that the students can download materials from the Internet

and have access to the Learning Channel, the graduation rate

has shot up to 70 percent. Some students have won science awards,

and many are applying for college. "I never thought the

sun could do all this," said Melusi Zwane, the school's

principal.

Myeka is a vivid example of

the impact of computers on society. But what makes this tale

stand out is the arrival of solar power. "It's the reason

for all that we have now," Mr. Zwane said. "Everything

comes from power." Myeka is a vivid example of

the impact of computers on society. But what makes this tale

stand out is the arrival of solar power. "It's the reason

for all that we have now," Mr. Zwane said. "Everything

comes from power."

Business has long been keenly aware of the potential of providing

energy to deprived areas. And interest in narrowing the world's

much-discussed digital divide, between the connected and the

unconnected, has only made the opportunity more inviting.

That is why energy projects like the one at Myeka High School

are not solely philanthropic. Though many financing hurdles remain,

there is money to be made, especially for solar energy companies,

when markets like these go online.

In fact, according to Strategies Unlimited, a market research

firm in Mountain View, Calif., for the solar industry, roughly

40 percent, or $1.2 billion, of the $3 billion worldwide solar

business last year came from rural markets like the Valley of

a Thousand Hills. In the United States, for example, solar has

had decent sales as an environmentally friendly complement to

the existing power grid, but there is a more immediate need for

it in rural areas. Strategies Unlimited predicts that the leading

companies in the industry, like the Royal Dutch/Shell Group,

Siemens, BP, Sanyo Electric, Sharp, Kyocera and AstroPower, will

continue to have revenue growth of about 20 percent a year from

these markets. That will make the remote rural market alone worth

roughly $2.5 billion by 2005.

Two billion people, roughly 30 percent of the world population,

are off the energy grid, living in areas without utility services.

And a billion of them have the means to pay for power, said Prof.

Daniel M. Kammen, director of the Renewable and Appropriate Energy

Laboratory at the University of California at Berkeley.

According to solar industry vendors and analysts, many of

these billion people spend $5 to $10 a month on kerosene, almost

exclusively for lights. Solar power, of course, has many more

uses, and by amortizing the start-up costs over perhaps five

years, the total cash outlay is about the same.

"There's a lot of money to be made in converting those

people to solar," said Dr. Allen M. Barnett, chief executive

of AstroPower, a publicly traded company based in Newark.

In July, for example, Shell Solar signed an agreement with

the Sun Oasis Company, a distributor in Beijing, to supply systems

for up to 78,000 households in rural western China.

Aside from selling directly to remote areas, solar energy

companies are expected to achieve much of their growth in powering

telecommunications companies that want to extend their services,

including the Internet.

"In some cases the economics involving off-grid power,

such as power generators, don't allow telecom carriers to go

further out," said David Dunsworth, director for power systems

of Hutton Communications, a Dallas-based distributor of telecommunications

equipment. "Solar allows them to do it."

Robert A. Freling, executive director of SELF, said, "There's

no question that telecommunications and computer availability

are major issues when trying to get communities online, but without

energy you can't even talk about those."

Solar power has become the energy of choice in many rural

markets, in large part because the price has dropped considerably

in the last few years. Prorating over roughly 10 years, the upfront

cost of solar panels and accompanying batteries gives the energy

a cost of roughly 18 cents a kilowatt-hour, competitive with

any off-grid power.

Moreover, solar energy has no moving parts,

unlike other renewable sources, including wind and hydro, which

makes it easy to maintain in areas where technicians are hard

to find. Moreover, solar energy has no moving parts,

unlike other renewable sources, including wind and hydro, which

makes it easy to maintain in areas where technicians are hard

to find.

Solar power's attractiveness off the grid, and an overall

interest among governments, corporations and international organizations

in bridging the digital divide, have put it in a sweet spot.

"I think getting people online in rural areas will be

a huge growth driver going forward for local solar companies,"

said Steve Cunningham, an investment officer for the Energy House

Capital Corporation of Bloomfield, N.J., one of several private

American equity firms that have millions of dollars to invest

in energy companies in rural markets in the developing world.

But big challenges remain. Though they can last for 20 years,

solar panels and batteries cost a minimum of $500 for a small

house. That would be a huge upfront payment for many people,

said Charles Gay, a director of Greenstar, a nonprofit group

based in Los Angeles that promotes the use of solar energy in

bringing remote areas online.

"Coming up with a viable financing arrangement is definitely

one of the biggest challenges," Mr. Barnett of AstroPower

said.

International organizations like the World Bank and the United

Nations Development Program have started to put money into projects,

and businesses, to help solve the financing problem.

Two years ago, the International Finance Corporation, the

private investment arm of the World Bank, began investing $30

million through its Photovoltaic Market Transformation Initiative

for solar projects in developing countries like India and Morocco.

But some people contend that even though these projects provide

power for remote areas, many people in those areas have more

pressing priorities than spending their scarce dollars on computers

and Internet access.

"Clearly, for those numerous people in the developing

world that are hungry or sick, food and health must take priority

over everything, even education," said Lester Brown, chairman

of the Worldwatch Institute in Washington.

But many people who are involved in solar projects say the

access to power can help deal with those issues, too.

In some remote villages, the economy is "a barter system

where they exchange crops for kerosene, kerosene for medicine

and things like that," Mr. Gay said. "You have to give

them the resources to transform themselves into a real currency-earning

society."

In Parvathapur, a remote village in south- central India that

is off the power grid, Greenstar is starting to find evidence

of that. Last year, Greenstar invested about $75,000 in solar

panels, computers and Internet access to provide the village

with money-generating tools.

The village now sells its music, art and calendars online

to customers who include expatriate Indians in the United States.

Fifty-five percent of the revenue now goes to Greenstar to pay

back the initial solar and infrastructure expenditure. "Within

four years, we expect to have recovered our investment,"

Mr. Gay said.

Once the money is paid back, Greenstar's share will fall to

10 percent, which will go toward financing other projects in

places like Jamaica, Ghana and the West Bank or future ones in

Brazil and Tibet. "It's a self- replicating finance mechanism,"

he said.

In return, villages like Parvathapur receive not only a way

to build a micro- economy for their music and arts products,

but also a tool to better support their principal source of income,

agriculture.

Mr. Gay said the village is using the Internet to learn the

most efficient times to plant and harvest crops and the best

markets in which to sell them. "The village is making more

money than before," he said.

Over the last two years, with a similar goal in mind, the

Grameen Bank has financed more than 30 rural communities in Bangladesh

for energy projects. It gives interest-bearing loans to people

in those areas to buy Internet connectivity products like solar

panels and phone equipment. Enough entrepreneurial activity has

emerged to achieve a 90 percent payback rate on the loans.

SELF has provided revolving-credit loans to various areas

for home lighting. When it comes to projects with fully integrated

Internet access, SELF relies on grants and does not have a specific

repayment plan. It says it hopes that some type of commerce arises

from the efforts.

Building such commerce appears crucial. Many vendors and project

managers agree that if a village cannot set up a business model

and generate enough income from the new energy and the Internet

access, it will eventually be in the dark again.

"I've seen it many times," Mr. Gay said. "If

the community isn't self-sustaining after a while, none of this

will work."

Copyright

2001 The New York Times Company

The online URL for this story (which requires free

registration with The Times) is

http://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/09/business/09SOLA.html

click here

to download a printable copy of this document

|